Water is such an everyday substance – you use water to wash, drink, make food; it is commonplace in our weather and rivers, and surrounds us in oceans. Its ubiquity is not only important for our environment: it is absolutely critical for life.

The big reveal: Beta galactosidase and cryo-EM

My final Structure of Christmas may look like an unremarkable enzyme, but it heralded the arrival of a game-changing method in structural biology.

My ninth (and final) Structure of Christmas is beta-galactosidase: a pretty run-of-the-mill enzyme that turns compound sugars into monosaccharides. When you put a special dye on it, it turns the dye blue (whee!). It’s a mainstay of molecular biology and millions of students have used it in countless experiments, both fascinating and mundane. It doesn’t have much of a ‘wow’ factor – it’s a solid member of a respectable family of sugar-cleaving enzymes.

What is so special about it is the way its structure was determined.

Continue reading “The big reveal: Beta galactosidase and cryo-EM”

Tropomyosin and actin: Move!

My penultimate structure of Christmas is actually two molecular partners, which work together to make muscle move.

Most of my Christmas structures have been separable units – some large, some small – that float around in cells or cell membranes. But to move physically, organisms need to have more at their disposal than some things floating in solution. For most life forms, movement is managed by proteins working together. A perfect example of this is the beautiful partnership between actin and tropomyosin.

Antibodies: Defend!

Once a parasite makes it past our outer defences, it encounters some seriously sophisticated weaponry. One of these is the ever-shifting antibody, my seventh structure of Christmas.

Every large organism – you included – is just a feast laid out for any parasite (bacteria, virus or beastie) clever enough to break in and access its carefully amassed energy. Throughout the Billion-Years’ Evolutionary War between hosts and parasites, the host has always been on the defensive, endlessly innovating to fend off invaders.

Vibrio cholerae: Attack!

My sixth structure of Christmas is out to kill human gut cells, with help from a human protein. But has it simply shown up (drunk) at the wrong party?

Interactions between two living organisms nearly always involve proteins. All proteins fold into precise, beautiful shapes, tweaked and perfected by evolution over millions of years to perform very specific tasks. In a successful interaction, two of these shapes will fit together perfectly – like a plug and socket – to make things happen.

The twilight world between chemistry and life

Viruses live in a twilight zone, somewhere between life and its ingredients. My fifth structure of Christmas emerges from that zone to wreak havoc on cattle: the foot-and-mouth-disease virus.

Consider the virus: a beautifully crafted set of molecules perfectly arranged to do one thing, and one thing only: subvert life forms to make more of itself. But what is it? Is it ‘alive’, in the conventional sense?

Continue reading “The twilight world between chemistry and life”

RuBisCO: the lazy, needy carbon fixer

The CO2-fixing RuBisCO, a respectable representative of life on Earth, is my fourth structure of Christmas.

If a Martian visited Earth and was asked to report back on the most important protein in our biosphere, quite possibly it would choose RuBisCO. As enzymes go it isn’t the biggest, but it is a very big deal. It is extremely common – every single plant and photosynthetic cyanobacterium is stuffed full of it – and it performs one of the most crucial reactions for all of life: “fixing” gaseous carbon dioxide into sugars and amino acids.

The mighty, mighty ribosome

Life starts with the ribosome: the tireless maker of tiny machines, and my third structure of Christmas.

All the myriad things our bodies do are carried out by tiny biological machines – proteins, mostly – each of which has a specialised function: move muscle, sense light, send message, make tiny machines…

Seeing the light: opsin

The second structure of Christmas is the membrane protein opsin, which allows us to perceive light.

Proteins that control the information going in and out of our cells are harder to crystallise than run-of-the-mill globular proteins, as they have both water-loving and fat-loving parts and are tricky to mass produce. Opsin, our second structure of Christmas, is one such molecule. It is situated on a special membrane in a specialised cell at the back of our eyes, and senses light.

The shape of our tears: lysozyme

If there is one protein we can say we know inside and out, it is the humble lysozyme, which we carry in our tears. This is my first Structure of Christmas for 2016.

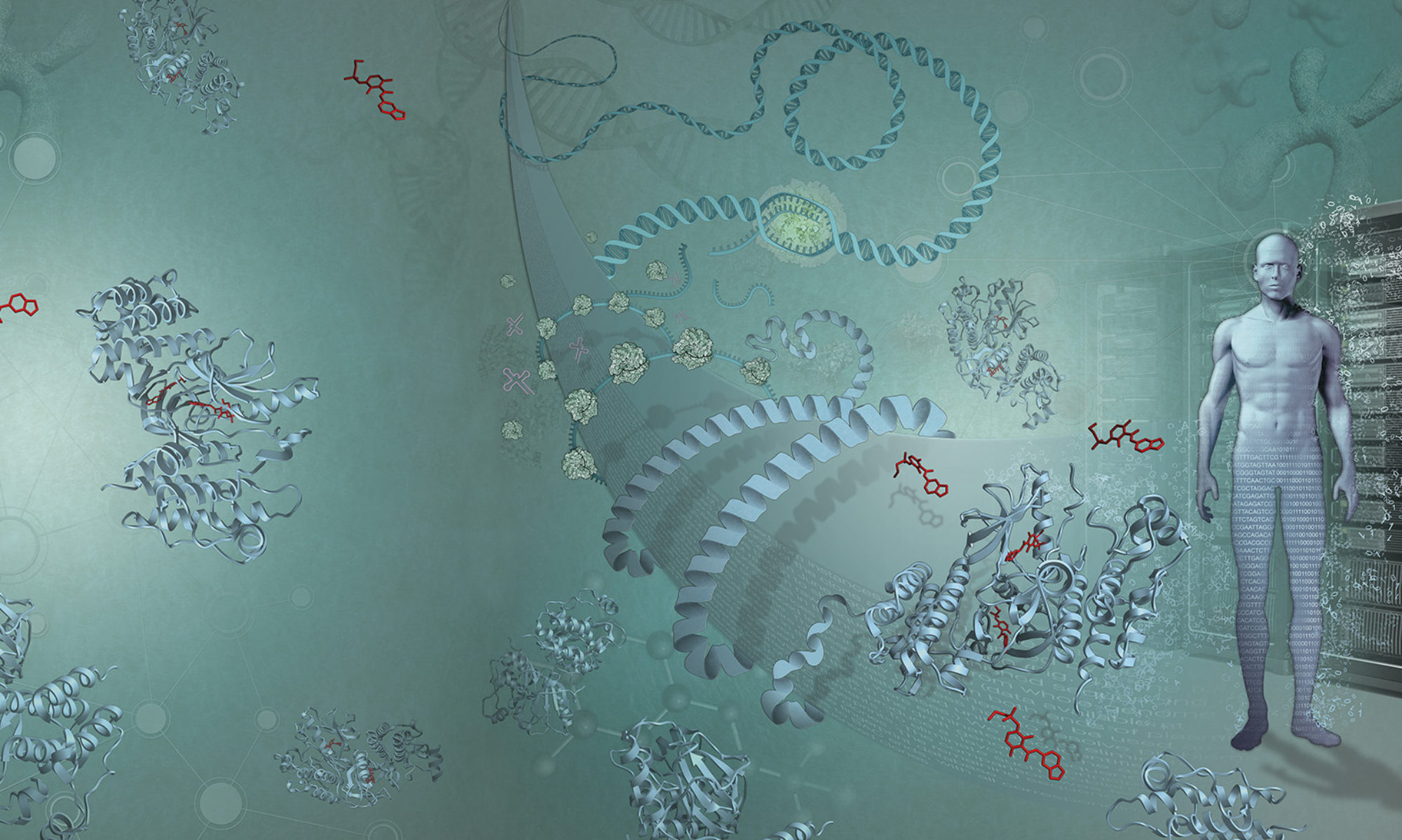

Nowadays, we can see the position of atoms as if we had vision millions of times sharper than human eyes allow. This is the gift of structural biology – the science of determining the 3D structures of molecules and correlating them with function. Structural biology gives us something more powerful than human vision, as the wavelength of ‘visible’ light is too long to resolve the position of atoms.